Thoughts on Algorithmic Fairness

Introduction and Overview

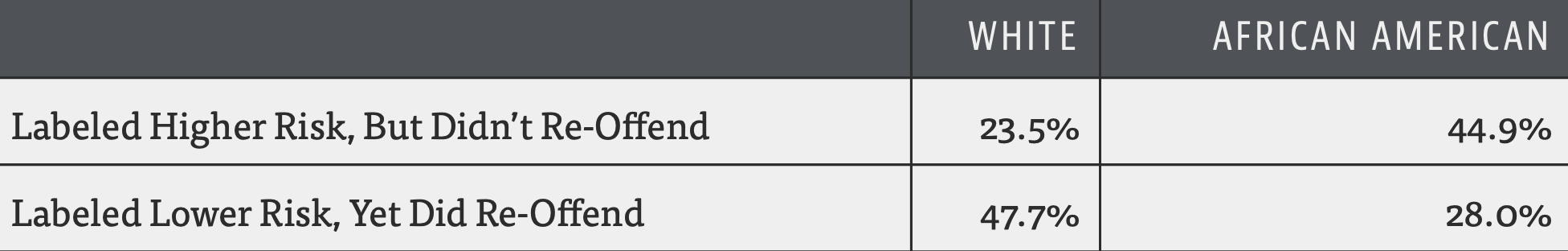

As research in machine learning is rapidly progressing, more and more decisions that affect our lives are being automated. These can be rather trivial decisions (e.g. which coffee brand is advertised to me online), but increasingly also more essential judgements are being handed over to algorithms, for example whether we are eligible for a bank loan in order to buy an apartment. If algorithms fail in such a scenario, the consequences for the individual are dire. The COMPAS case is arguably the most prominent example of such algorithmic decision-making failing in systematic ways - in an extremely high stakes scenario. The COMPAS (short for Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions) algorithm is a predictive justice tool by for-profit company Northpointe used in the US to evaluate risk of recidivism, i.e. how likely a criminal is to re-offend. The tool is used by judges in their decision making on parole, sentence length etc. Investigative journalists at ProPublica discovered in their famous 2016 study [1] how Northpointe’s algorithm is racially biased: it more often underestimates risk of re-offending for white people and overestimates it for African Americans.

Pro-publica’s work brought the problem of Algorithmic Fairness and Bias into the spotlight and started a heated debate within the general public as well as the scientific community. Computer scientists (along with statisticians, law scholars and political and social scientists) responded quickly with attempts to fix those biases. A community on Algorithmic Fairness formed and is steadily growing, publishing a large body of research for example through ACM’s conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency being held yearly since 2018 [2].

As scientists, much of their early efforts went into defining what is actually means for an algorithm to be “fair”. Such fairness metrics can be roughly divided into three categories: criteria based on group fairness, individual fairness and causal criteria (see info box).

For illustration, we use gender as the “protected attribute” with respect to which fairness is to be analysed.

Individual Fairness: “Similar individuals should have similar outcomes”. If student A and B have the same GPA, they should either both be admitted or both not be admitted, no matter their gender.

Group Fairness: “ Demographic groups should have similar outcomes”. An equal amount of men and women should be admitted, even if this means different GPA thresholds for male and female students.

Causal Fairness criteria: “The protected attribute should not influence the decision”. The outcome doesn’t matter as long as the gender has not explicitly been used to arrive at the decision.

Researchers then go on to think about ways to achieve such fairness criteria. One approach is to manipulate an algorithm’s training data by upsampling any underrepresented groups in the dataset. Alternatively, one can modify the algorithm itself. For the above example of college admission, this could mean decreasing the required GPA for a certain subpopulation in order to obtain a diverse student body.

Criticism of these approaches

Lately, this type of work has faced a fair amount of criticism. Two arguments come up repeatedly: Firstly, there is what I call practical criticism: It’s impossible to quantify a complex concept like fairness, and interestingly, even if we seem to succeed, we often produce inconsistencies between the different fairness criteria discussed above. This can be formally proven in incompatibility theorems like the ones presented in [3]. Here’s an intuitive argument for why individual and group fairness can contradict each other: Imagine a university is admitting students solely based on their final high school GPA. Women had slightly higher grades on average. If we try to respect individual fairness our admission algorithm could simply be a threshold, grade > t, applied to each student in the exact same way. Because of the difference in grade distribution, this would mean more women than men admitted - a clash with group fairness.

Computational, quantitative methods aren’t sufficient to solve deep ethical problems. We have tried since at least the 17th century, when Leibniz attempted to formalize a calculus of reason that would allow us to solve any argument, especially a moral one, by pure logic deduction:

“The only way to rectify our reasonings is to make them as tangible as those of the Mathematicians, so that we can find our error at a glance, and when there are disputes among persons, we can simply say: Let us calculate, without further ado, to see who is right.” [4]

Yet we disagree about the most basic questions - a richer language than what the formalisms of mathematics provide seems to be necessary to encapsulate the ambiguities and, sometimes, contradictions inherent to moral discourse.

Secondly, the algorithmic fairness community is accused of lobbying for big tech. Large corporations are very interested in the topic: Famously, Google founded (and immediately shut down) an ethics board in 2019 [5] but continues to work on the topic [6]. Other examples are their AI daughter company DeepMind with its Ethics & Society group [7] as well as Microsoft’s efforts [8]. All of these companies sponsored the above-mentioned ACM conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency in 2020 [9], and it’s worth taking a closer look at their motives. Certainly, many of the individuals working on such questions in a corporate setting do so, because they acknowledge the huge responsibility and importance of their work and are committed to working on safe and ethical technologies. As profit-seeking companies, however, they certainly have other driving forces as well, an important one being their reputation. “White-washing” their algorithms and attempting to turn them into ethical technologies, however, has another major advantage for big tech companies: By performing small technical adjustments to their products, they can hope to circumvent regulation through laws. As Rodrigo Ochigame phrases it: “The majority of well-funded work on “ethical AI” is aligned with the tech lobby’s agenda: to voluntarily or moderately adjust, rather than legally restrict, the deployment of controversial technologies” [10]. Academia is at danger of becoming complicit in this: “Silicon Valley’s vigorous promotion of “ethical AI” has constituted a strategic lobbying effort, one that has enrolled academia to legitimize itself.” [10]

He argues that this is not a new phenomenon. Historically, socially unjust decision procedures have often been justified with statistical objectivity. [11] As an example, credit scoring (i.e. banks evaluating whether or not an individual is eligible for a bank loan) used to be based on personal interviews which were supposed to evaluate an individual’s ‘character’. An outcome of such an interview is of course influenced by the interviewer’s individual opinions and thus very vulnerable to possible biases they hold w.r.t. race or class. In the 1960s, such interviews started to be replaced with statistical calculations of credit scores, which inherited their human designer’s biases. When a ban of credit “scorecards” was proposed in the 1970s within the framework of anti-discrimination legislation, their producer Fair, Isaac & Company argued the statistical objectivity of such methods in order to demonstrate compliance with the definition of fairness in the law [11]. Like today, by reducing issues of discrimination and injustice to statistical calculations, we are at danger of cutting out important aspects of such complex moral and political questions, and are possibly standing in the way of urgently necessary regulation of automated decision making technology.

A defense of our attempts

Despite this valid criticism, I find technical work within algorithmic fairness valuable. It is useful for researchers to try and morally evaluate their work in order to make sure it aligns with their values. Of course, as computer scientists, quantitative methods are the tools most accessible to us, and I do think there is great value in phrasing ethical questions in the language of our community. This should be done avoiding the reductionist trap - always having in mind that ours is just one way to look at the problem. Fair ML research should not be carried out as an alternative to solid law-making efforts. Rather, as computer scientists, logicians, statisticians and alike, we should aim to support such efforts, and to translate between social science, law, philosophy and the computational sciences. An example of this “translation” approach is Martin Mose Bentzen’s work on formalizing classic philosophical concepts for use in robots, e.g. in his paper “A Formalization of Kant’s Second Formulation of the Categorical Imperative” [12].

The discussion of whether or not research on ethical AI and fair machine learning has its place can be embedded in the much larger discussion about the moral responsibility of science. Are science and technology neutral and their moral value purely determined by some application or user, or do we as scientists carry a responsibility?

References

[1] https://www.propublica.org/article/ machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing

[2] https://facctconference.org

[3] Dwork, Cynthia, et al. “Fairness through awareness.” Proceedings of the 3rd innovations in theoretical computer science conference. 2012.

[4] Leibniz, G. W. (1951), Leibniz: Selections, P. P. Wiener (Ed. Trans.), New York: Scribner, p. 51. – cited from https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/let-us-calculate-leibniz-llull-and-the-computational-imagination#fn13

[5] https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-47825833

[6] https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/fairness-overview

[7] https://deepmind.com/about/ethics-and-society

[8] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/ai/responsible-ai

[9] https://facctconference.org/2020/sponsorship.html

[10] https://theintercept.com/2019/12/20/mit-ethical-ai-artificial-intelligence/

[11] Martha A. Poon, “What Lenders See: A History of the Fair Isaac Scorecard” (PhD diss., UC San Diego, 2012), 167–214.

[12] Lindner, Felix, and Martin Mose Bentzen. “A Formalization of Kant’s Second Formulation of the Categorical Imperative.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.03160 (2018).